ICES Decision to Increase the 2014 North East Atlantic Mackerel Quota based on Expedience rather than Science

We have no experience from the past of what will happen to the Western component of the (North East Atlantic mackerel) stock should this undergo too much fishing pressure. The quality of data particularly on the fishery is therefore crucial for accurate stock assessment.

John Simmonds, Pelagic News, 2001.

Over the last few summer seasons, this writer has experienced a marked decline in both average size and numbers of mackerel scomber scombrus encountered while rod and line fishing inshore coastal waters along Ireland’s east coast. Struggling to catch a couple of dozen mackerel in areas where once the species was prolific, especially during July and early August, appears to have become the norm, certainly post 2010.

To create confusion, while sea angling off exposed rock marks on the Beara Peninsula, West Cork in late June and again during late August 2013 mackerel of a fine stamp were encountered in reasonable numbers. Returning to the east coast, during September of 2013 mackerel swam inshore and hung around for close on three weeks. Smaller then those landed in south west Cork and not quite as prolific, have North East Atlantic mackerel become less abundant or is their late arrival due to a change in behavioural patterns?

Since 2010 Iceland, the Faroe Islands, and Greenland have cumulatively extracted 250,000 – 300,000 tonnes per annum over and above the agreed quota for North East Atlantic Mackerel, a quota which is currently the preserve under a 2008 agreement of Norway, certain EU nations and Russia. This development, given that the prescribed “sustainable” quota is backed by thirty years of science and fishing experience, has rightly concerned both the industry and environmental groups.

Reflected or so it would seem in the dearth of mid summer mackerel off Bray Head, Co. Wicklow, is the scarcity of mackerel on Ireland’s east coast linked to this recent escalation in commercial landings and if so can the existing stock prevail given the level of attrition? On the other hand, does the relative abundance of mackerel along Ireland’s south west coast imply that the North East Atlantic mackerel stock is in better shape then was previously thought?

Taking an historical view, back in 1974 a working group established by the International Council for the Exploration of the Seas (ICES) convened for the first time in Copenhagen. This expert group was set up in response to the imminent collapse of the North Sea mackerel fishery, which had declined from an estimated 4.3 million tonnes in 1964 to 550,000 tonnes by 1970.

A direct result of the Norwegian purse seine fishery taking at its peak in the late 1960’s an unsustainable 900,000 tonnes of North Sea mackerel per annum. The spawning stock biomass subsequently fell to 100,000 tonne give or take by 1985 and the fishery collapsed (Simmonds, 2001). To this day it has not recovered.

Both Government and Industry at the time recognised that the serious decline in North Sea mackerel had occurred due to limited scientific data on the species. The newly established working groups brief was to reduce this knowledge gap, with the result that most of what is known about North East Atlantic mackerel dates from this period.

Initial tagging experiments by the working group identified two distinct stock elements, Western and North Sea, which spawned in the Celtic Sea in March/April and the southern North Sea in June/July respectively, both these stocks mixing during the winter off Shetland.

Subsequently to aid research on spawning biomass the western stock was further subdivided into southern and western elements. Today the western component accounts for 78% of the spawning stock with the North Sea spawning biomass still remaining low at 3% or a little over 100,000 tonnes, where post exploitation in the late 1960’s as stated it amounted to a hefty 4 million tonnes.

The southern component presently amounts to 19% of the overall stock, a percentage which would be much higher but for over fishing in the 1970’s which eventually led to the establishment of the Cornish “exclusion” box.

Becoming operational in 1980, the Cornish box was and still is fully closed to all methods other than quota regulated vessels using hand lines or gill nets since 1985. Recognised as a nursery area with a juvenile population that can reach up to 80%, the Cornish box is perceived as important to western stock recruitment.

To compliment tagging and laboratory analysis of mackerel, triennial (every three years) egg surveys were initiated. Results of egg surveys conducted through the late 1970’s established the Western spawning stock biomass (SSB) at approximately 2.7 million tonnes, subsequently adjusted upwards based on fishing mortalities to approx’ 3.2 million tonnes. The advice on fishing catches (F) was agreed at 0.15 or 15% of the stock equating to a total allowable catch averaging 520,000 tonnes, a figure which was substantially exceeded regularly during the 1980’s and 1990’s.

This increased exploitation of a species, destined predominantly for human consumption, resulted in illegal industry practices such as high grading, misreported catches, unreported landings, and the slipping of nets. These four problems were attributed then, and still are within Government and Industry reports, to quota restrictions as opposed to being recognised as the deliberate actions of individual skippers. By slipping nets (releasing fish by opening the net at the side of the boat, most of which will die), or grading fish onboard, skippers maximise their return on effort by landing only marketable fish.

As more adult fish were removed through commercial fishing the increased percentage of juveniles represented within the overall stock reduced fecundity and this in tandem with large annual catches served to shrink the western spawning stock (SSB) by the early 1980’s to 1.6 million tonnes a feat repeated in the early 2,000’s.

Sadly, given the ingenuity, passion, levels of innovation, entrepreneurial spirit, and drive displayed by many who entered and developed what is a vital and relevant arm of the commercial fishing sector, greed has too often prevailed to the detriment of both the resource and those who work their livelihood playing by the rules.

Greed manifested not only by the illegal industry practices outlined above but also in the multi million fraud cases exposed in the mid 2,000’s. Cases such as the £63 million “Shetland Catch/Peterhead fraud involving Scottish skippers, and separately the alleged €40 million fraud where three quarters of the total Irish pelagic fleet of twenty three vessels were reported by the UK authorities to have been involved in illegal landings to the same Peterhead factory cited above (Fishupdate.com, online, 2007).

When one analyses the official landings recorded through the late 1990’s and early to mid 2000’s, the period when these scams where taking place and marry them to the decline in spawning stock biomass, an illustration of the damage being wrought on the resource is all too clear. By 2002 official landings were nudging 800,000 tonnes. A rough calculation dividing the cumulative monetary value of the known fraud by the then price per tonne for mackerel gives a figure in excess of 100,000 tonne of illegally caught mackerel on top of the official catch.

It is no wonder that the spawning stock (SSB) fell to 1.7 million tonnes in 2002, half a million tonne below the precautionary level of 2.2 million tonne, a figure set by ICES which was subsequently agreed as an element of the 2008 ICES management plan by Norway, the EU, and the Faroe Islands.

Fast forward to 2013/2014 and even allowing for the increased catches way above quota which forced the Marine Stewardship Council to remove the North East Atlantic mackerel fisheries sustainability status in 2012, and a maximum quota of 542,000 set by ICES for the same year, ICES decided not to give advice due to apparent inconsistencies in the assessment modal used up to 2012, but instead supported an increase in quota of 864,300 tonnes for 2014 based on:

- Spawning Stock Biomass (SSB) appearing to be increasing despite recent high catches.

- The geographic spread of North East Atlantic mackerel appearing to widen.

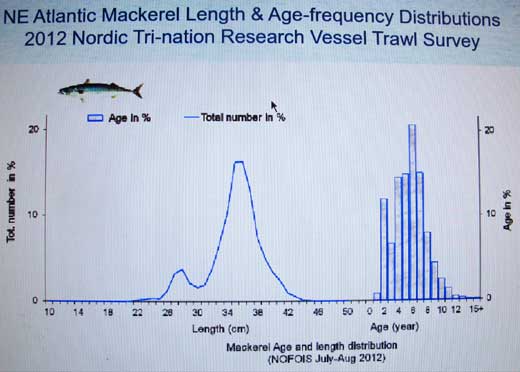

- The International Ecosystem Summer (combined trawl sweep) Survey in the Nordic Seas (IESSNS) 2013 report which indicated strong year classes for 2010 and 2011 and that the North East Atlantic mackerel stock may have been underestimated and could actually amount to 8.8 million tonne.

However ICES also advocated caution based on:

- Insufficient understanding of the mechanism driving the estimated increase in stocks.

- If the apparent increase is due to productivity how long will this last?

- Estimates of uncertainty from egg surveys are likely to be under represented.

- Swept survey estimates do not provide any coefficient variation (CV) estimation.

This apparent U turn can be linked to a 2010 published academic paper entitled, “Investigating agreement between different data sources using Bayesian state-space models: an application to estimating NE Atlantic mackerel catch and stock abundance”. Without doubt a “Bayesian” approach to estimating mackerel stocks whereby one gathers information from a wide grouping of sources is the ideal, and new evidence from the IESSNS survey is coming to light. However, given that the data collected has still to be verified it is hard not consider that expedience to all those countries presently fishing mackerel governed the final decision by ICES to increase quota.

Fisheries management like economics is not an exact science, and economists do not as is the common public view make forecasts, they just analyse historic trends and events advocating possible solutions based on what worked historically. In a lot of cases, Ireland’s banking crises a case in point, economists such as Morgan Kelly and David McWilliams got it right pre September 2008 only the political and business establishment did not listen. The same unfortunately can be said of fisheries.

After the collapse of the North Sea component of the North East Atlantic mackerel stock and the establishment of the ICES mackerel working group post 1974, science has consistently placed the spawning stock biomass of North East Atlantic mackerel at 2.2 million tonnes give or take.

Yes the industry will always want more return on their investment, lobbying and utilising any scrap of evidence that enables this desire. However, the last thirty years have shown that management of the fishery relative to the science has worked enabling a multi million euro industry and the jobs it provides to exist while extracting a whopping average of 500, 000 tonnes plus of mackerel annually.

If the SSB has indeed been set too low over the period extending from the 1970’s to date then what it has done is allow for the vagaries of both man and nature. There are too many examples world wide of fisheries going into severe decline due to malpractice, political expedience, and science trying to gain every extra ounce of yield through employing the principals of marginal analysis.

What historical research of the North East Atlantic mackerel fishery clearly shows is that possible underestimating of spawning stock biomass in terms of long term fisheries management has worked for all vested interests to include industry, environmental, and recreational over a protracted period of time. The fisheries management modal one could argue actually bucks the modern trend where declining stocks are the norm.

Catches amounting to 900,000 tonnes per annum reduced the North Sea mackerel stock from 4 million tonne to a never recovered 100,000 tonne back in the sixties. ICES should not forget this, listen to its heart and dramatically reduce the North East Atlantic mackerel quota back in line with historical assessments for 2015, as 2014 will be the forth year in a row that close to 900,000 tonnes of mackerel (a significant dark magic number) will be removed from the North East Atlantic. Unless the decision makers have forgotten, remember both the early 1980’s and 2000’s as the industry will not thank you when it all goes pear shaped.

Ashley Hayden © January 2014

References

Andrews J, Nichols J (2013) PFA North East Atlantic Mackerel Fishery Surveillance Report, Moody Marine Ltd.

Fahy E, (2013) Overkill! The euphoric rush to industrialise Ireland’s sea fisheries and its unravelling sequel.

ICES WGWIDE, North East Atlantic Mackerel, Report 2013.

Jansen T, Campbell A, Kelly C, Hatun H, Payne MR (2012) Migration and Fisheries of North East Atlantic Mackerel (Scomber scombrus) in Autumn and Winter. PLoS ONE 7(12): e51541. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0051541.

Lockwood S J, (2012) North East Atlantic Mackerel, A Review of Stock Status and Prognosis, Coastal Fisheries and Conservation Management.

Marine Conservation Society, North East Atlantic Mackerel Fishery, Position statement, February 2013.

Marine Institute, The Stock Book, 2013.

Marine Institute, The Stock Book, 2012.

Marine Institute, The Stock Book, 2011.

Molloy J, (2004) The Irish Mackerel Fishery and the Making of an Industry, Killybegs Fisherman’s Organisation Ltd and The Marine Institute.

MSC Fishery Surveillance Report, The Danish Pelagic Producers Association, North East Atlantic Mackerel Fishery, Report N. 2010-0007 Revision 00 – Date 19.07.2010, PP 1 – 16.

Simmonds, E. J., Portilla, E., Skagen, D., Beare, D., and Reid, D. G. 2010. Investigating agreement between different data sources using Bayesian state-space models: an application to estimating NE Atlantic mackerel catch and stock abundance. – ICES Journal of Marine Science, 67: 1138–1153.

Simmonds J (2001) North Eastern Atlantic Mackerel Stocks, Pelagic News.

See also: Understanding the North East Atlantic mackerel fishery.